I once met a woman on the Syrian border who had spent several decades in Tadmor prison in Palmyra only emerging when ISIS had taken the town. I cannot verify her claim but she said she gave birth to her child in its dark dungeons underground, that child did not see the sunshine for seven years, and whilst she hated the Islamic State, she hated the Assad regime more. Nevertheless, for the region and the international community, Assad, is the better partner. He is a known quantity, better the devil you know as opposed to rebels with Jihadists in their midst. He can be dealt with using tried and tested policies of the past. In many ways, the Jihadis present themselves to be a greater conundrum in the region and indeed in the Muslim world as a whole. Assad is slowly but surely corralling the rebels and Jihadis into that province to finish them off. I doubt however, that he will, if the example of the Nigerian President Muhammad Buhari’s is anything to go by.

In 2015, Mr Buhari claimed that Boko Haram or the Islamic State in West Africa was ‘technically defeated’ but after three years, its fighters are still hiding in the borderlands of Niger, Chad and Cameroon, 27, 000 dead and 2 million civilians displaced. The lesson being that fighters are far more adept at surviving than civilians and they will most likely escape. These Jihadis will present themselves to be a greater problem not only for the international community but also for the Muslim world as a whole. Estimates of foreign fighters vary from four thousand to forty thousand foreign fighters in Syria. There will be security experts scratching their heads asking what comes next and what should one do? And I don’t mean to be pessimistic here, but I am not so sure there is a clear answer to solving the problem because the phenomenon of Salafi-Jihadism is part of a historical process that will have to be played out to its fullest extent. In many ways Salafi-Jihadis share similarities with the Jewish Zealots and Sicarii from fourth century BC; these Jewish extremists ignored established religious leaders, they were aggressive militarists unwilling to follow the Rabbis who were trying to come to a political solution with Rome. That sort of behaviour seems uncannily similar to Salafi-Jihadis. They seem to represent that strain of militancy within the Muslim world which is torn between coming to an accord with the West and resisting Western interference in its countries.

Admittedly, meeting Salafi-Jihadis fighting in Syria do have their peculiarities. In theory, they are meant to be absolutely devoted to their word, if they give you Amān, that is a promise of safety, then you are safe. In reality, they might just change their minds mid-way and then you’re screwed. Even if you convert to Islam your fate may just be the same. The conversion of Peter or Abdul Rahman Kassig didn’t prevent him from being killed. According to Jejoen Bontink, a former Belgian ISIS fighter, James Foley and John Cantlie, too had converted to Islam. How sincere their conversion was irrelevant in the circumstances. In the Islamic faith as soon as one utters the profession of faith one is as sinless as a new born babe, and one has full rights as a fully-fledged member of the Muslim community, the Ummah. One thing you cannot do is to test how much someone, especially new converts, believe. But clearly these hostages who had ostensibly pronounced the Muslim testimony of faith hadn’t been believed and were not granted those privileges that was incumbent on the Salafi-Jihadis. Instead they were tortured and executed brutally. From a Salafi-Jihadi perspective their lives should have been spared but this is when modern pragmatism intrude; they were white Westerners, fetched top dollar and would most certainly make the front pages; in such circumstances religious considerations could be fudged and put aside.

Now, of course, visiting these zealots I had a lot of things going for me. I was brown and Muslim, two qualities which in the circumstances worked in my favour. Perhaps, if I was taken as a hostage, I might not be as marketable as say a white journalist in an orange suit. I might not fetch as much in terms of a ransom, and there might even be a risk that no one would believe me to be a hostage. I can just see the Jihadis debating my fate saying: ‘what they think he is one of us?! But he is nothing like us.’ All that was needed was for the Press to lump me in with your bog standard Jihadi and I’d face the Mesut Özil ordeal: the dreaded multiple identity predicament where I had to prove that I wasn’t like ‘them’, that I loved the Queen and her damn corgis. I can just see that tweed screwing up his face and inspecting my dirty straggly beard going ‘hmm, is he really a journalist, dear? He certainly doesn’t look like one to me’. How am I meant to look? I have languished in prison, the beard has grown beyond hipster length, my hair is flea ridden; at best I could pass for a Salafi-Jihadi Count of Monte Christo; at worst Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s cousin. Even if I declared my love for Queen and country I would still confirm every single prejudice of the Tweed, ‘well you never know, does he drink wine? No Chardonnay? Oh dear.. oh dear…’.

This might just be a feeling, I don’t know why, but I just feel that the money wouldn’t be as forthcoming. I’m not saying the media is racist, I have a load of journalist friends but those who know, know! But then again the creative amongst the Salafi-Jihadis might just think that all of us are scum and might propose that I appear as an extra in their latest release: ‘The Spy who got blown up in the Cold’. They will find a macabre yet creative way to send me away to my Maker. So you have to be careful and take your precautions when you go to meet Salafi-Jihadis.

So I made sure I catered for their peculiarities, as I scrambled across the border, I stopped smoking. I had stopped smoking from the age of fifteen and had given up frequently. Sometimes I stopped for years and then when the feeling betook me, usually when I was in the Middle East, when cigarettes were dirt cheap, the food was good, coffee was bitter and the sun was out I would just grab one from a friend and soon enough I’d be finishing off a pack of ten by late afternoon. But whilst I usually agonised about giving the cigs up which I inevitably did, filming this group of fighting Jihadis gave me just that added incentive to stop immediately in case some of them didn’t like my terrible habit. I just didn’t want their ‘sincere’ advice to turn into something else where they saw me as a brazen sinner contravening the laws of God and I found myself walking round London without the ability to stick two fingers up at a white man van. Salafi-Jihadis are an unpredictable lot. Thankfully, apart from the odd cigar, I have remained a non-smoker. Curiously, thanks to my experience with Salafi-Jihadis my belief in the existence of God has also been strengthened.

Prior to my visit I was messaging one of these Jihadis and he condemned me for not fulfilling my individual obligation to fight jihad. I tried to explain that I was a journalist, journalists don’t fight. But this particular fighter who had a world vision directly proportional to his educational career which ended at the age of fourteen, threatened to kill me for offering such an excuse. His reasoning ran thus: By not fighting I had become an apostate and thus my blood was legitimate to slay. Or perhaps he was just angry suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder like many fighting men do. Men shouldn’t spend too long a time fighting, it makes them unbearably hard.

But Providence had contrived that I should bump into that self-same Salafi-Jihadi who had threatened me on that very trip into Idlib province. And as I got off the motorcycle in the market thinking that my worst nightmare was coming true, there he was standing smiling at me warmly, his large frame hugged me and asked me for forgiveness for threatening to kill me.

I hugged him so hard as if I was hanging on to dear life and I forgave him totally. Only God could have contrived such a thing and so my faith in God was strengthened. Now, of course I should add a caveat, the men I covered were by no means mere Jihadi zealots, there were all sorts of fighting men. The good, the bad and the ugly. And it struck me that they represented various aspects of the future of Jihadism especially relevant to countries that are faced with the Jihadi conundrum whether in Syria, Tunisia or Nigeria.

Ostensibly, there are three types of fighting Jihadi and I will cover each in turn. The pop-Jihadi who can easily be dealt with by the current security apparatuses. Then there are the Committed Jihadi and the Master Jihadi, those two are going to be far harder to deal with.

Some of these fighting men, the foreign ones at least, struck me as following the standard pop-Jihadi trope. They espoused the language of the Jihadism born from Afghanistan, their English accents had become tinged with Arabic. They, to my amazement, even used ‘thus’ and ‘narrated’ and so forth in daily life thinking that this made them more intellectual. But I want to be fair, these pop-Jihadis were not devoid of sincerity but they struck me as vacuous souls, predictable, unaware of who they were, and caricatures of who they wanted to be. They thought themselves to be lions when in actual fact they were just about everything in between; some were serious, some were comic, some were thugs, some were absolute gents and some were indeed as courageous as lions when the fight kicked off. I suspect they were the same sort of men you might find in the British Army and could be made to do anything providing they had the right military officer. If they had a good officer all was well, a bad one could spell a Mai Lai massacre.

They were the sort of men who had killed and then nonchalantly said that the men they had killed were murtadd (apostates) so it was fine to shed their blood, and they didn’t lose any sleepover it. Whenever an organised military force push, it is these types that disappear into the ether, they will hide in the nooks and crannies of Turkey or Chad whiling away their time. And then when the coast is clear they return to their home countries grizzled and weary telling the intelligence officers at the border that they had been on holiday in Dubai and think nothing of their experience. Except perhaps years later, when they comprehend the enormity of what they have done and they have to live with the consequences of their actions. You hope then, that Dostoyevsky’s idea will ring true: that living with the crime is bigger than the punishment, for many pop-Jihadis will get away with murder.

There were other fighting men of course, the committed Jihadis, they were slightly older; Brits and Europeans who loathed social media, they wanted to protect the sincerity of their actions by not announcing them to the world. They appeared moved by the religious impulse and knew that their religious devotion should not be corrupted by bombast and showing off. They maintained that they fought only for God, not a political ideology, and it was paramount that these ideals be kept secret to protect their pristineness. These men intrigued me. They wanted to fulfil an obligation that they believed was incumbent on them. I met two Indians from Bangalore – an engineer and an accountant. Both men struck me as deeply pained by what was occurring in the Muslim community. But the question was how were they to express their wish to serve the Muslim community? They talked about how think tanks and the media, not wholly incorrect I should add, did not bat an eyelid as Jewish young men and women fulfilled their desire to serve their community in Israel but Muslim men were labelled otherwise.

But Jews had a state, they had an army with a semblance of military discipline, these Muslim men did not. They seemed trapped by modernity that invalidated their desire to ‘serve’ if you will, and also trapped by their traditions and stories, which espoused coming to the aid of their fellow Muslims. This theme was constant; the thread runs in Netflix and in Muslim salvation history. The hugely popular Turkish drama series Ertugrül is based on the historic founder of the Ottomans who came to the aid of the Seljuks against Byzantine incursions. Muslim Facebookers post the example of the Abbasid Caliph Mu’tasim Billah who, according to legend, went to the aid of a captured Muslim woman. Muslims swim in the history of this obligation and there is an immense guilt felt by the devout for their impotence and emasculation.

Muslims have never seen themselves as a people who turn the other cheek after all, historically they were a fighting peoples, of empire, of power, culture and civilisation. Take the example of the polymath and West African scholar, Sheikh Uthman Dan Fodio who declared himself the leader of the faithful and established the Sokoto caliphate in the nineteenth century when the powers that be prevented Muslim religious devotions from being practised. The caliphate lasted till 1903 with the arrival of the British. These are powerful examples for Muslim youth.

But what about now? Exactly how should and can this impulse of Muslim young men be manifested in this day and age? In the past young men could go off to a Ribat, Sufi frontier fortress or if one lived in the Ottoman period join the Bekhtashi order with its close connection to the Ottoman army, to fight and worship at the same time. But the world is no longer a world of empires. There isn’t a Muslim foreign legion, nor is there a caliphate. Nation states have been carved out of the Muslim world. Geopolitics and Western countries have already made it clear that the prospect of a resurgent Islamic State is a frightful prospect, and yet, there are still Muslims bleeding. And so the argument from current Muslim ideologues runs thus: this wouldn’t happen if we had a Muslim state, if we had our own government, if we had our own army, if we applied our own laws, if we did all this God would give us victory and succour. And the young quite naturally reply: ‘how do we achieve that?’ And they reply: ‘through blood, the rose isn’t got except by putting one’s hand on the thorns.’ So how are young Muslim men to express this sentiment? The young see Western armies in the countries of their fathers.

Facebook posts and rants are extremely unsatisfying; and so young Muslim men grapple with this conundrum. And as long as this question isn’t resolved amongst Muslims they will not be at peace, and the language of Awlaki and Bin Laden will pull in Muslims from all over the world now that Pandora’s box has been finally prized apart. It seems that the only language available to the young is the Jihadi militancy of al-Qaeda since any other sort of protest isn’t validated nor understood.

This sentiment of young Muslims or geist if you will, cannot be combated with platitudes, ill thought out deradicalisation programmes and naff websites set up to combat social media.

What many of these well-intentioned leaders and Imams don’t realise, and I have seen this with my own eyes, is that radical preachers like British Islamist, Anjem Choudhury, and Yemeni militant, Abu Baraa, have a constituency. They hit a nerve and are watched by some of these Jihadis in the heart of Syria rather than those they deem to be ‘scholars for dollars’ despite the vast difference in learning. There is a dissonance between the young and the imams. Anjem Choudhury is not religiously trained, he’s a solicitor. Abu Hamza al-Masri is self-taught but when the no doubt erudite Azhari sheikhs such as Ali Gomaa seemingly support Sisi’s killing of innocents followed up by Habib Ali Jifri’s support for his teacher, one cannot help but understand their predicament and anger. Religion it seems, is being used to keep the young tame and docile. Same goes for the late Ramadan Buti, the ‘Shaykh of the Levant’, and indeed Sheikh Bin Bayyah, the Mauritanian professor of Islamic Studies, and his American student Sheikh Hamza Yusuf Hanson, who have adopted a Burkean position of being against revolution preferring the stability of authoritarian monarchies and seemingly support a kingdom such as the United Arab Emirates seen by many as actively subverting the aspirations of millions of Arabs and Muslims for their own political ends, one can see why these young men will continue to fight.

The issue is not that scholars can’t work with the state, one of the Hanafi legal school’s major jurists Abu Yusuf is celebrated for it, but when scholars don’t act as their flock’s lightning rod, or do not convey their sentiments to power, or are not sufficiently independent enough, the matter becomes hopeless and young men being young men, look for other avenues. When Father Gapon was killed, young Russian men and women looked for other avenues. Currently, surveying the Muslim world, Muslims are bleeding all over the globe. My Facebook feed is filled with images of Hindus killing a Muslim for the sake of two cows, an eight year old Asifa Bano getting raped, horrific images of Rohingya, innocent Mali Fula villagers killed in cold blood by hunters on the premise of anti-terror operations, not to mention Syria and Palestine – these news feeds have a profound impact on the soul of anyone who calls himself human, it affects even a cynical grown man like myself, what then of the young ones? So you see these men are going to be the grist for the mill. These men will stay on and hide in the nooks and crannies too but they won’t return to their home countries. They will weather the storm and wait for that man who can organise them effectively.

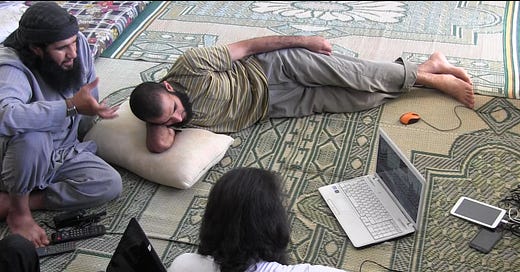

And amongst these men is the Master Jihadi, for he holds the key to organising them. I have not met many like that but the one I found, quite by chance, in the guesthouse where I was staying in Idlib province. Abu Muslim was altogether a different sort of Jihadi: an everyman. In contrast, pop-Jihadis took pictures of themselves, sported all the paraphernalia of war, posted it on Instagram and fooled themselves into thinking that this was proselytising Islam. When in all reality, their hearts skipped a beat every time some follower ‘liked’ something they posted, Abu Muslim was nothing like that. I only met two people like him, one was a senior al-Qaeda figure, who I didn’t even want to shake hands with in case some drone decided to release its weaponry and obliterate me and the other was Abu Muslim. Abu Muslim, that is what he called himself, was different precisely because he was so ordinary. The Levantine Arab you saw standing next to you when you caught a servis or greeted you in the cafe. You’d pay him little regard unless he asked you for directions. The only distinguishing feature was his generous beard and hair that gave clues to his religious affiliation, otherwise he wore a T-shirt, track suit bottoms, sandals, a sun-bleached cap and a pair of glasses perched on his nose. Your paths would probably never cross. He could have been an agricultural worker from Homs or a tailor in Cairo, but it was the glasses I suppose, that gave him that engineering mien. I saw him riding pillion criss-crossing the town going from one place to another always on the move meeting important men. That’s all he did all day.

And though he was never the Emir of the guesthouse I stayed in, there seemed to be an unspoken consensus that he was indeed its undisputed Emir. His suggestions seemed to be carried out. His men too didn’t have that typical characteristic Jihadi look, none of those things were displayed on his closest followers. Two of them were beardless with open faces, they wore jeans, t-shirts, had their hand guns stashed discretely in the back or just slung lazily on the coat hooks when they weren’t outside. They played with the cats, talked about such and such but generally they were as obscure as you could possibly think. If they sat in a minivan going through a checkpoint, the guard would probably let them pass thinking they were local barbers or worked in the market. I don’t know if that was the reason they sported that look but they certainly embodied it. They were curious men, friendly and often asked me what the world outside looked like.

Whenever Abu Muslim came in to the guesthouse I saw how they got up, not because he was an Emir, but because he was their older brother and they just made sure that he was okay. And he did the same. When he saw signs of tiredness in me and in the men, Abu Muslim reached for the lemons growing in the garden, grabbed some ice from the fridge, squeezed the lemons, crushed them, added sugar and made us a drink reminiscent of a virgin mojito. Whilst I knew something of the other men, he seemed very illusive. I only caught his story from snatched snippets of conversations at the end of the day when I was putting my equipment away. He had kids tucked away somewhere safe. He moved unhindered or seamlessly through the Levant as if borders weren’t even an issue. He had a technical background. When the guest house had a visitor or two, these brothers sat in a circle exchanging stories that only fighting men shared, but ultimately it was him they had come to visit. I got an idea of his importance when a visitor, a young fellow with a short beard, came in, shook hands and joined his two companions in the verandah waiting for him. He was like all of Abu Muslim’s men, Palestinian. The three men were soon joined by a Maldivian fighter, the visitor asked about one of his countrymen he had fought alongside a long time back. The Maldivian Jihadi informed him that he had had been martyred. The visitor smiled, sighed and said he was brave in a short statement that served as a eulogy. Silence. Death had intangibly brought them closer. The other two men recalled some other events and it became apparent that each man was a seasoned fighter. I was told much later that the visitor had been close to Abu Muhammed al-Jolani, commander of the Syrian militant group Tahrir al-Sham, perceived as some sort of legendary figure by the men, and I guessed that perhaps the Palestinian had some business with Abu Muslim, and he did.

On one of the days I was working I realised that my GoPro was missing. There was a suspicious voice within that convinced me that maybe one of the men I was sharing the room with had stolen it. GoPros are expensive and moreover, very useful for filming combat footage for propaganda films. Of course I didn’t express those sentiments openly but I did ask if anyone had seen the camera. Abu Muslim just said it was impossible that it could be taken. It was as if he guaranteed it. He insisted that I take my backpack apart, that it would be there, somewhere in my bag. He was absolutely certain that the GoPro was there, he believed in the integrity of his men. He was right, late in the evening when I did unpack everything I found the camera exactly where it was. I felt ashamed of thinking so badly of my hosts.

In the evening Abu Muslim served us some Kebse a Levantine rice biryani type dish. He brought it out from the dark kitchen and put the large round dish on the verandah where all of us sat down together to eat. I could only liken him to a doting mother, not a father. I heard the creaking sound of the iron gate open and one of the Palestinians brought over two cooked chickens that had been steam cooked so that their flesh were succulent and fell off the bones.

Abu Muslim invited us to eat but felt that I was too shy with the food, he chucked in bits of chicken to my side of the large steel dish as all the men sat round eating the food chatting. It was crude but exactly how I would have expected him to behave. After the meal they prepared some tea and I saw Abu Muslim relaxing and that’s when I asked him what his story was.

Surprisingly Abu Muslim was not shy in telling me that he was a master bomber. Of course I couldn’t confirm his story, but according to Reuters, in March 2012, Damascus experienced two car bombs that killed twenty seven and injured a hundred. The cars had targeted the headquarters of the Syrian Airforce intelligence services and the Criminal Police Headquarters.

Syria had fifteen such spy agencies competing with each other to make them supremely effective and brutal. They had been responsible for killings on an industrial scale. Abu Muslim had succeeded in destroying them both. The Syrian regime held al-Qaeda affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra responsible for the actions but it was Abu Muslim and his boys that did it.

‘For three years I was the most wanted man in Syria’, he told me satisfied as if it was a badge of honour. I didn’t know how to feel about the bombings. On one hand revulsion twenty seven people had been killed and a hundred people had been injured. They could have been officers or they could have been innocent bystanders, all of them irrespective of their sectarian affiliations, would be leaving behind loved ones. On the other hand, I had spent a day inside the very intelligence headquarters that he had blown up. Syrians said that those who go in never came out and they considered my return a miracle. But I am Swedish and so the rules are very different for me. Nevertheless, they had hounded me for six months and changed me into a different person, due to their constant surveillance, harassment and spying in Damascus. I can live in a police state but I also know when a man hasn’t lived in one when he belittles the freedoms we have in London. In Fara’ Filistine they had presented me with a thick file asking me where I had been on such and such place, what my post-graduate research was all about and so on. I saw intelligence officers masquerading as Salafis complete in their kufi and thobe, and I heard the screams and shouts down the corridor whilst I was served tea and cigarettes having genteel conversations with my interrogator. Everyone knew that the Assad regime was a real police state worthy of an Arthur Koestler novel. Some of my friends had disappeared during my stay in Damascus. So I certainly understood why it was blown up.

Abu Muslim told me that the whole project had been a partial success. He had planned to launch various simulated attacks in the Golan and Lebanon to provoke an Israeli response and attempt to start a regional war. When the Syrian state would fail to respond to Israeli aggression it would show the Muslim world what Syria really was: a sham and the people would rise up and overthrow it. I didn’t know what to think of Abu Muslim, was he a demented megalomaniac or was there something of the 20th century revolutionary in him?

Abu Muslim was a son of history and geopolitics. He hadn’t learnt his bomb-making skills from al-Qaeda but from his older brothers who were Salafi-Jihadis fighting the Israelis. He had been fighting Israelis in his mother’s milk, he didn’t know anything else. Had he been born earlier maybe he would be learning his trade with the leftists and the Abu Nidals of this world but it so happened that his older brothers were Salafi-Jihadists. The Abu Muslim would never go away.

When the Syrian uprisings broke out, Abu Muslim went to Syria like Castro’s Cubans did to Angola, and offered his services. There seemed to be cross-pollination of sorts between his aims and al-Qaeda, and maybe he had become al-Qaeda or perhaps parts of al-Qaeda had become a little like him. I couldn’t quite figure out where exactly that convergence had occurred, but at the same time what exactly was he and what did he represent?

Here was a man whose rage against the Israelis could be understood by all, but he was from the Western perspective at least, on the wrong side of the fight, acceptable only if he renounced political violence against the Israelis. But for Muslims, Abu Muslim is not a wholly unsympathetic character, he has some sort of constituency if you will, especially in the Middle East. And so he presents himself as a conundrum for Muslims, was he, Abu Muslim, an expression of modern Jihad? The future of asymmetric warfare? Or was he none of those things? An aberration? The Martial tradition within Islam would always exist but was Abu Muslim an expression of just that? Or was he doing something that many of us would do if we were put in those circumstances?

Had Abu Muslim been a classic pop-Jihadi, al-Qaeda type figure with all his zealotry, Abu Muslim would present himself as less of a question. But in the following days when Islamic State released their latest video, the whole town went crazy trying to buy enough data to be able to download it and watch it. It was like a movie release or some Fortnite update. One of the men in the guest-house obtained the gigabytes and now all the men sat around the laptop watching the film. It was a surreal experience. Whilst the pop-Jihadis sat round memorising its nasheeds (devotional songs) and played the film over and over again like demented psychos watching it with an immature glee, Abu Muslim watched it like a political scientist. After the film, I asked him what he thought of the Islamic State. He said that they had an admirable project, that only they had a vision to build a state. That, to his mind, was a good thing. He believed that Muslims needed a state to take them out of their humiliated position. Muslims needed to determine their own destinies, all of that had echoes of anti-colonial rhetoric not jihad.

‘What will you do if they start fighting other Muslims?’ I asked, ‘then I will put my guns down and stop fighting. I didn’t come here to kill my fellow Muslims.’ Yet again here was the Abu Muslim conundrum: he was a crypto-Islamic State supporter, not affiliated to them, not bent on global Jihad, not bent on fighting other fellow Muslims and yet the man justified the bombing of two intelligence headquarters knowing full well that there would be civilian casualties with Muslims amongst them.

Now that the Islamic State is on its last legs, one would expect that it is the end game for the likes of Abu Muslim. But the Islamic State might be a flash in the pan yet the Jihadis have shown the Muslim world that colonial borders are not fixed. I suspect that there will be many men like Abu Muslim dreaming of the Hummers breaking the Sykes-Picot border and laying low in nearby countries waiting and planning to give an expression to their political ambitions that cannot be expressed in the current geo-political climate or the Salafi-Jihadi project. It will be these men who will no doubt cause the future problems for the power-brokers of the region.

I suspect the bombings in Suweida in July 2018 which led to the loss of 200 souls too had someone like Abu Muslim as its planner. Men like Abu Muslim have the expertise, the grievance and a degree of sympathy from a population who knows the dungeons of Middle Eastern dictators that will enable the likes of him to survive. The pop-Jihadi will disappear in to the ether but men like Abu Muslim and his followers will remain in the Middle East, North Africa and indeed West Africa and will continue to plague the Muslim world and the West for many years to come.

This article was first published CM19 in April 2019. For those reading this as a forward, my name is Tam Hussein an award winning investigative journalist with a particular focus on conflict. The Blood Rep is my newsletter that covers security, jihadism, militancy and criminal networks. Do read my latest book The Darkness Inside

.

Zane, thank you. 1. I don't believe that any version of Islamic State will satisfy them precisely because they are puritans/purists, which means there will always be men within this group who will deem it not to be 'islamic' enough. I don't think Mecca and Medina need be part of that, as historically many have been set up outside of the Hejaz. The final, question, I don't think they will be contented by a Muslim version of Mossad etc. Remember AQ was meant to be that Special-Ops vanguard that could go in and out to support the Pan-Islamic community. Thank you for reading Zane.

Do you believe there is any version of an Islamic state that would satisfy these men and undo the "humilaited position". Like the Zionist fixation on Jerusalem and the Land of Judah would this hypothetical state have to be centered on Mecca and Medina or could any other location fill this role? Would any form of revolution or reform in the Saudi state provide the opportunity to scrath that itch, could these men be contented by joining some Islamic version of the Mossad, with clandestine state-sponsored missions to right percieved crimes against the Ummah, targeted special-ops with less collateral unlike their current style of indisriminate bombings?

PS: A deep thanks for your efforts in shedding light on the psyche of Salafi-Jihadism