Letter to the Revolution: Syria’s Jihadi Dilemma

A personal exploration of the Syrian revolution's moral complexity. The tension between revolutionary and jihadi narrative, and the blurry space in between.

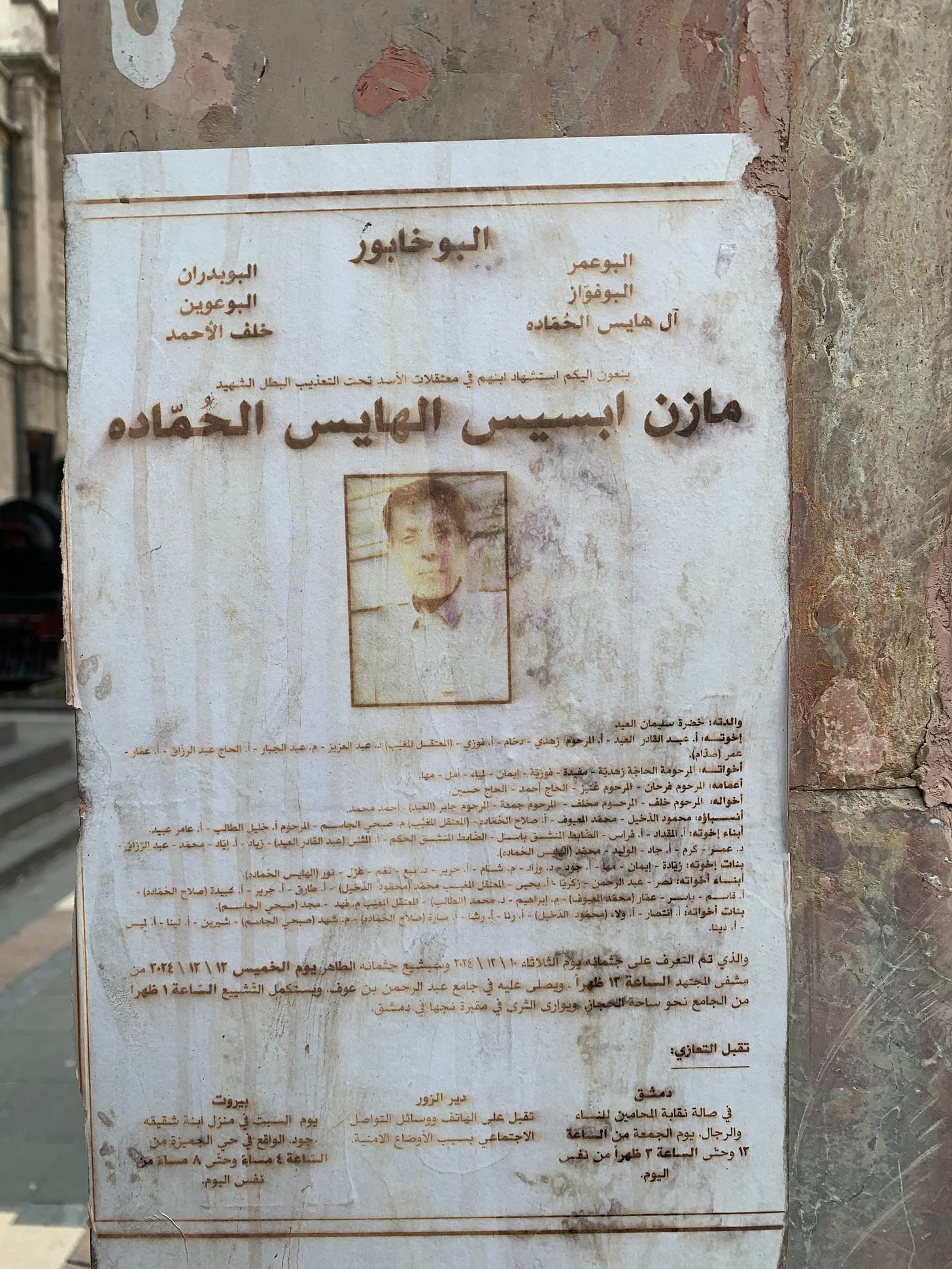

A few days after the fall of the brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad, I was in Damascus reconnecting with old friends. The capital was in a state of revolutionary euphoria and nation-building. There were activists on the steps of the historic Ottoman-era Hijaz Railway Station talking about the country’s future. Among the faces of the dead and missing Syrians plastered on the wall was the gaunt, boyish face of activist Mazen Al-Hamada. He had been killed just ten days before the regime fell. Al-Hamada was a prominent human rights activist who exposed torture in Assad’s prisons.

In Homs, a small city in the north, the mother of Abdel Baset Sarout, the Syrian national goalkeeper turned rebel, was serenaded by demonstrators. Sarout was a beloved revolutionary icon known for his defiant songs. He symbolised the early, peaceful uprising before taking up arms. In the cafés of Rawdah and The Ivy, where Syria’s intellectuals often meet, the national story was of a wholly Syrian character. It went something like this: in 2011, the Syrians demonstrated peacefully against the great tyrant after a group of teenage boys were tortured to death for writing anti-government slogans. What followed was fourteen years of unspeakable brutality—barrel bombs, sectarian violence, and chemical attacks—until the Syrian people overthrew the dictator. In many ways, Hamada and Sarout were the poster boys of this national story. They were the clean ones who epitomised the Syrian national struggle.

But I realised that there were also less clean men who were considered heroes. These figures belonged to another, uncomfortable revolutionary story. One evening, I met Hassan Idlebi in the salon of Sham Hotel. Idlebi was an intellectual in his forties, a former fighter, a father, a husband, and an old friend. It had been years since we last saw each other. When we met, he hugged me warmly, touched my beard to point out the greys that had sprouted. He had fought in the conflict, yet his bright, open face showed none of the signs of time. “You know,” he said, as if he had come to correct the record, “you are wrong about Ali. His virtues outweigh his mistakes. He was a lion.”

It was such an odd remark. Had he come all the way from the north just to tell me about Ali—a Londoner, several years dead? It felt as though Idlebi had come to share another national story—one far more complex, dark, and savage, but just as much a part of the revolution. Without Ali’s contribution, Idlebi seemed to suggest, the victory of Damascus would never have occurred. His story could not be ignored. It was visible in the markets of Damascus, where vendors sold Syrian rebel flags alongside the black-and-white flag associated with jihadist groups—groups Ali had joined. That white flag, once associated with the Prophet Muhammad when he went to war, is now tied to jihadist factions aligned with al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other militant groups. The simple reality is that Syria’s national story travels through capitals like London and other cities. It is far more complex than the romantic version told by the intellectuals sitting in Rawdah Cafe. At the heart of this story lies a dilemma Syrians must resolve if they are to move forward: how to reconcile not just the nationalist side, but also the jihadi side of the revolution.

I didn’t know how to feel about Ali. He made headlines when he was killed by a Russian drone in 2019 in Idlib, a key rebel stronghold in northern Syria, and, if I’m honest, I wasn’t sad to see him go. Maybe even a little relieved. His friends posted pictures eulogising him and the British press picked it up. After all, he was part of Britain’s own national story—the first homegrown jihadi executioner to make UK headlines.

In 2013, his passport was found in a car riddled with bullets at an Assad checkpoint. It crystallised every fear the British state held about radicalised British Muslim men going to Syria to join jihadist groups. Ali represented the worst fears of governments across Europe and beyond—young, often alienated Muslim men leaving home to fight in Syria. These foreign fighters were not motivated by Western ideals like democracy or nationalism, as seen currently on Ukraine’s battlefields, but by archaic religio-political values long since buried in a secular Europe.

The likes of Ali represented not just a security threat, but a destabilising force—across Europe and beyond. At the time, though, to me, he was just the wayward kid brother of a friend—someone who, it must be admitted, helped launch my career. I’m still mostly seen and heard in that context, as many of us brown journalists often are.

As the conflict progressed, I began to see him as someone who had tarnished the message of the Syrian people—a message that had once been understood around the world. Yet here was Idlebi, a man in his forties, who described him as a lion, as if he were some kind of hero from an Icelandic or Norse saga. Ali seemed to belong to an alternative national story—one that extended beyond the songs, the U.S. Senate hearings, and the demonstrations. I was intrigued by that.

“They,” said Idlebi, referring to the Syrian revolutionaries, “are trying to airbrush history. It was the jihadis who won this war, whether they were foreign or Syrian.”

***

I met Ali in Damascus in 2008. His older brother, a close friend of mine, had asked me to speak with him, as I had previously worked as a youth worker. Ali was a British-Syrian caught up in the gang life of Acton, West London. When we met, I immediately liked him—he was lost and loyal, but also the kind of person who could get into a fight with a lamp post. I used to visit him at his mother’s flat in Darayya, a suburb of Damascus, and we’d talk late into the night.

After that brief sojourn in Damascus, he returned to London. One night, he called me and admitted he had messed up—he was on remand for assaulting an elderly man while drunk. Around the same time that Ahmad al-Sharaa, the Syrian president and former al-Qaeda militant, was languishing in an Iraqi prison, Ali, too, was locked up in Feltham Youth Offenders Institution in West London, where I visited him.

Prison radicalisation is often blamed for turning young Muslim men—British or Iraqi—towards extremism. But I don’t believe that was the case with Ali. If anything, religion grounded him during his reckless episodes inside, as he openly admitted in the letters he sent me. His handwriting was neat—typical of someone who had left school at twelve. The letters were sincere, full of spelling mistakes, and peppered with Quranic verses and Prophetic sayings.

After his release in 2009, he visited me. My firstborn had just come into the world. We would meet on a park bench in Hyde Park, where he shared his aspirations of starting a business. As soon as he got his driving licence, he planned to buy a van and launch either a carpet cleaning or removal company. During those conversations, Ali often spoke bitterly about his troubled relationship with his father, a retired bus driver. He described his father as a difficult man with a fiery temper.

When the Syrian conflict began in Deraa in 2011 and protests spread across the country, Ali’ personal revolution began. Though he wasn’t especially political, he followed the events closely. Bashar al-Assad’s brutality shocked viewers across British television screens. The conflict quickly turned violent: his mother’s hometown, Darayya, was shelled, and Assad committed some of the revolution’s earliest massacres there. The fall of two other dictators—Qaddafi in Libya and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt—made the prospect of Assad’s downfall feel like a real possibility. History appeared to be on the side of the revolutionaries.

But Ali wasn’t drawn to Syrian nationalist slogans; instead, he was influenced by jihadism. By then, Britain had experienced two decades of jihadi ideology propagated by preachers like Abu Qatadah and on internet forums like at-Tibyan.

Moreover, Syria occupied a special place in the Muslim sacral imagination and had galvanised Muslims around the world. Greater Syria—also known as the Levant—encompasses modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. It is not only regarded as the land of the prophets but also as the place where many apocalyptic events will unfold in Islamic tradition. Ali, then, was nourished by a completely different narrative from that of Sarout and Al-Hamada.

Ali lived in an area frequented by many jihadis. He worshipped at a mosque run by Khalid Rashad and a Syrian imam, Abdul Hadi Arwani. The latter was a fierce critic of Assad. He fled to the UK after being sentenced to death as a teenager because he photographed events in 1982 when Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad, crushed an uprising in Hama.

Ali told me he looked up to Rashad—and I could see why. When I visited Rashad years later for a separate story, he exuded an old-country Jamaican charm and had an easygoing rapport with the younger generation. As YouTube videos show, the mosque witnessed many young converts taking the shahada—the Islamic testimony of faith—at Rashad’s hands. Many future jihadis attended this mosque, including Mohammed Emwazi, Alexanda Kotey, and El Shafee Elsheikh—the ISIS execution squad dubbed by the media as “the Beatles.” These men killed journalists in cold blood in front of the world.

As I discovered much later, the mosque had also been attended by several fraudsters who ran the notorious jihadi Instagram account Rayat al-Tawheed, which both captivated and horrified the British media. Ironically, these fraudsters operated the account from Kurdistan, in northern Iraq.

In March 2012, Nassim Terreri—a young British-Algerian from west London—travelled to Syria with a friend, posing as a journalist. He was killed by Assad’s forces. His death opened the floodgates, inspiring a wave of foreign fighters from west London. Terreri’s fate showed these prospective jihadists that travel to Syria was possible, and so the exodus began.

The only problem was that Ali was broke. To fund his journey, he teamed up with some local raqis—spiritual healers who performed Islamic exorcisms and were running a lucrative hustle. According to Ali’s future wife, these charlatans and hucksters were affiliated with the radical British Islamist group Al-Muhajiroun and were unable to find work due to their lack of education and/or criminal records. Instead, they peddled black seed oil, herbal remedies and Quranic verses to women with mental health issues, squeezing as many dinars as they could out of them. Some of these raqis were directly responsible for sending these vulnerable women to Syria.

By 2012, Ali told me he had become a person of interest and was being monitored by the British security services. They had even warned him that they were aware of his plans to travel to Syria. But at some point, they must have lost track of him—or perhaps they let him go deliberately, hoping that such "undesirables" would be killed abroad, thereby solving the problem.

Ali had even begged me to take him along when I went to cover the story in 2012. He said he wanted to help Syrians and atone for the sinful life he had lived. I told him he was on parole, that he could seek forgiveness from God here in the UK, and that his religious duty was to care for his sick mother.

But Ali didn’t listen. He made a dummy run to France, and when it proved successful, he travelled on to Syria—violating his parole and leaving his ageing mother behind. Ironically, the man who helped him get to Syria was none other than his local imam, Arwani. Arwani was later murdered by Khalid Rashad in a dispute over the mosque’s ownership.

In January, Ali left behind a letter to his family and took a circuitous route into Syria. By then, the war had turned violent, savage, and deeply sectarian. This shift was largely due to Syria’s demographic and political makeup: while the majority of the population was Sunni Muslim, the ruling elite belonged to the Alawite minority—a sect of Shia Islam. This group was heavily supported by Iran and its proxy, Hezbollah, a Lebanese Shia paramilitary organisation. When Hezbollah entered the conflict on the side of the Assad regime and its Alawite paramilitaries, the revolution, almost inevitably, took on a sectarian character.

On the Sunni side, Ahmad al-Sharaa had entered Syria with just five or six companions. Within a year, his group—an al-Qaeda affiliate then known as the Nusra Front—had grown to five thousand fighters. Syrians were learning the art of war on the fly: storming army barracks with hunting rifles, handling explosives provided by Lattakian fishermen, and studying YouTube videos uploaded by Palestinian militants. Their makeshift battalions formed, bloomed, splintered, and shared their exploits on Facebook in the hope of attracting donations.

In many ways, they were as fragmented as the Syrian political opposition, which itself was fractured across capitals like Cairo, Doha, and Istanbul, each faction vying for leadership. The arrival of the jihadis was a turning point—they brought with them a level of military discipline, ideology, and combat experience that changed the course of the revolution.

These jihadists were a mix of Chechens who had fought the Russians, former Afghan veterans, and fighters from Sharaa’s Nusra Front. They brought with them a wealth of combat experience—graduates, so to speak, from the insurgency schools of Iraq, Russia, and Afghanistan. Their arrival gave the revolutionaries an edge in battle and, for a time, served the revolution’s goals.

The jihadis could fight. They were zealots—willing to die for their cause—and they pushed Assad’s forces back. Operating like elite units, they trained local rebels in military tactics. But the alliance came at a cost.

The revolution’s message, once clear—the people want the fall of the regime—was now complicated by other ideological agendas. Many jihadists wanted Syria to become an Islamic state governed by Sharia law. By 2015, even Sarout had reportedly considered joining ISIS. Gradually, the revolutionaries fell under the orbit and influence of the jihadis. Many became homegrown converts to the jihadist cause—and many remain so to this day.

Ali joined the fray at the height of the ideological splits and internal divisions within jihadist groups. After receiving basic training—mostly from Albanian and Balkan fighters—he went on to fight in Hezbollah strongholds like Quseir, as well as in Hama, Latakia, and many other locations.

As he told me in 2015, “I have done a lot of killing, but it’s okay because they were apostates.” I remember thinking at the time: How had he judged his victims to be apostates? Who gave him the authority to take their lives?

The savagery and thuggery that had made Ali a misfit in London turned out to be an immense asset on the battlefields of Syria. What had rendered him unfit for civilian life made him perfectly suited to the brutality of war. He reminded me of Ali La Pointe—an Algerian revolutionary and former criminal who became a key figure in the FLN’s anti-colonial war against France. La Pointe’s capacity for violence and his willingness to enforce the FLN’s commands were the main reasons he was recruited. He would go on to play a pivotal role in the Battle of Algiers in the mid-1950s.

In May 2013, Ali’s passport turned up in a car that had been riddled with bullets by Syrian regime soldiers—making headlines in the British press. Shortly afterward, he contacted me to confirm he was still alive. At just 22, Ali seemed to be thriving in that environment. While many British jihadists were getting killed, he proved surprisingly resilient. He told me he was holding people up in the north—ransoming and robbing them, much like he had done in London.

Later, he appeared in Rayat al-Tawheed propaganda videos, executing nameless Syrians and Shiites, and asking if there were more he could kill. In the footage, he’s seen firing a Glock and chastising British Muslims for staying home and enjoying Nando’s while he was, in his words, “helping his brothers and sisters.”

British intelligence later used voice and facial recognition technology to identify him as the perpetrator. The Ali I had once known was now wholly unrecognisable.

My own correspondence with Ali took a dark turn. Over Kik, a messaging app, he would lecture me about my supposed obligation to fight jihad. He was becoming increasingly extreme. In one of these exchanges, he excommunicated me. In his eyes, I had left the religion of Islam—and so, I deserved a death sentence. He claimed I was failing to fulfil the obligation of jihad, which, he insisted, was an individual duty on every Muslim. He quoted the Palestinian scholar and spiritual godfather of global jihadism, Abdullah Azzam, and threatened to kill me the next time he saw me.

I was deeply shaken. But the experience also motivated me to work on the book To the Mountains: My Life in Jihad, from Algeria to Afghanistan—a memoir by Abdullah Azzam’s son-in-law about the jihad against the Soviet Union. I doubted whether Ali would ever read it, but I know that many young Muslims did—and found it immensely beneficial.

In 2015, while I was riding pillion on a motorcycle in Saraqib—a small town in northwestern Syria—filming, I unexpectedly bumped into Ali on the street. At that moment, I genuinely thought I was a goner. As I dismounted and the rider went to greet him, Ali flashed me a gold-toothed grin. He was a bear of a man—towering and broad—yet his warm hug suggested he had either forgotten about the death sentence he had once issued, or chosen to ignore it. I was quite content for it to remain buried in his forgetfulness.

Ali told me he had joined another hardline al-Qaeda affiliate, Jund al-Aqsa. From my interviews with its members, it was clear they held him in high regard. He now rode around in a pickup truck—something he could never have afforded in London—with a gun holster strapped to his side. With his long hair, thick beard, and rugged appearance, he looked wild, yet completely at ease in his surroundings.

We sat down to eat kebabs with a Dutch ‘celebrity’ jihadist, Yilmaz Israfil, who—bizarrely—proposed that we make an MTV Cribs–style documentary about his life. He even suggested I could pay him by gifting him an expensive watch, just as an American news channel had apparently done.

I told him, somewhat amused, that under UK law such a gesture would be considered funding terrorism. I explained that people in the UK had been convicted for sending bottles of perfume to their sons—so a project like that would never pass an editor’s scrutiny.

After my chance encounter with Ali, his wife escaped and returned to the UK, leaving behind what she alleged was an abusive marriage. Living in a bedsit in South London, she claimed he was deeply traumatised by events from both his childhood and the war.

I had also heard recordings of him sobbing like a child, recounting how many people—including women and children—he had buried and lost. While her accusations might be dismissed as those of a scorned woman, they included deeply disturbing allegations: that Ali had opened fire on a van full of civilians—an act strictly forbidden in Islam.

According to her, Ali had become a Syrian version of Colonel Kurtz from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. She claimed he kept the teeth of his victims in a box as war trophies, and stored recordings of his killings on his phone, which he replayed again and again. It was behaviour that seemed to align more with that of a psychopath than a soldier.

In 2017, the UK—deeming Ali a security threat—stripped him of his British citizenship. By then, he had attempted to join ISIS and had been arrested by al-Sharaa’s new group, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which had formed after al-Sharaa publicly broke with al-Qaeda in the same year. Ali was eventually reconciled with them.

In 2019, he was killed by a Russian drone strike. His death made headlines in the UK, and many of his friends wrote eulogies in his honour. Idlebi said they “talked about him as if he was a saint.”

I didn’t know how to feel about his death. Was the world a better place without him?When I raised the allegations against him, Idlebi simply replied, “His virtues outweigh his mistakes.” But how could he overlook the van full of civilians? Or the box of teeth? How could Ali, in reality, be—as Idlebi maintained—a “giant cuddly teddy bear”?

Idlebi was a student of warfare. He explained that, above all else, Ali possessed an unparalleled bravery—one that could change the tide of a battle. He told me that Richard the Lionheart had been responsible for the massacre of 2,700 men in cold blood at the Siege of Acre in 1191, and yet there is a statue of him outside Parliament. Was there really any difference between the two men?

Amongst fighting men, it seemed that bravery trumped all. Ali, he said, could break the line and turn the outcome of a savage battle in their favour. This ability to deliver victory—this singular trait—made even his most terrible flaws tolerable in war. And now, the jihadis and the rebels have won. That, Idlebi argued, was why Ali was a hero. It wasn’t Mazen or Sarout who brought victory, but a roadman from Acton—or the crack Turkistani and Syrian jihadis who supported Ahmad al-Sharaa’s push to Damascus.

And that, I suppose, was the answer. To men like Idlebi, Ali, and others in their world, value was measured on a different scale. Just as a boxer might judge another man not by his wealth or education but by his ability to inflict pain, so too did these fighters assess worth through a lens of battlefield utility. What we might consider psychopathy or savagery, they saw as assets.

And, as Idlebi pointed out, this way of thinking is not so far removed from our own society. “Why do we celebrate Mike Tyson, Sonny Liston, Jake La Motta?” he asked. La Motta, after all, was notorious for his brutality both inside and outside the ring—yet Martin Scorsese made a film about him, starring Robert De Niro.

In the world Idlebi inhabited, Longfellow was right:

Meekness is weakness,

Strength is triumphant

Over the whole earth.

In the end, war is a brute expression of power.

Now that the battle’s won and the songs have ended, Hassan and I sit in a plush Yemeni mandi restaurant in the heart of Damascus, sharing a plate of steaming rice and chicken. As we eat, we reminisce about the old days—some book we read, some pretty girl we were in love with, our love of boxing and how our lives diverged.

We talk about Ali—how, if he were alive, he would fare in this new country. Would he join us in Rawdah Café, like in the old days? Or would he sit restlessly, jangling those teeth in his pocket, or scrolling through battles of yore on his phone? How would one feel introducing one’s firstborn to ‘Ammo Ali—Uncle Ali—again?

Could he cope with the mundane? When going to the market, would he be like the war veteran James in Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, unfulfilled by civilian life and destined to return to the battlefield? The trouble is, Bigelow’s protagonist had a place to expend his energies. Where does Ali expend his?

Maybe Ali is a hero now simply because he has passed. Perhaps the same dynamism and energy that once defined him could now scupper the peace. In this tapestry of revolution, where exactly does Ali belong? Hassan Idlebi and the Syrian jihadis can now begin to rebuild their homes, raise their children—they can step into the national story. But what about the likes of Ali? Could he return to a normal life—would he even know what that means anymore? How does a fledgling state, desperate for stability, reckon with figures like him—men who were the very tip of the spear that delivered victory? And should the state blunt that spear, especially with so many anti-regime elements still in their midst?

Ali is a dilemma. Somehow, the nascent Syrian state must find a way to reconcile the two contradictory strands of the revolution: the national story and the jihadi story. The former craves stability; the latter demands expansion. How the state might achieve this remains unclear. Perhaps it’s not even possible. But one thing is certain: for any attempt to succeed, the state needs both stability and time—and it is short on both.

Regional powers like Israel and Iran are working to balkanise the country by exploiting ethnic divisions. What they may not realise is that such tactics can backfire. In that kind of fractured landscape, the forces most likely to emerge victorious are the jihadis. They have had over a decade of practice managing savagery and are more comfortable operating in grey zones and volatile conditions than most. If Ali were still alive, he would likely thrive in such an environment. Perhaps he’s only ever at peace when he’s fighting. So maybe it is wise for the international community to get behind the country—before others fill the vacuum.

For those reading this as a forward, my name is Tam Hussein an award winning investigative journalist with a particular focus on conflict. The Blood Rep is my newsletter that covers security, jihadism, militancy and criminal networks. Do read my latest book The Darkness Inside.

Phenomenal exploration. Your ending on the "management of savagery" hits the nail on the head. The jihadists have always been at home in that environment. Let's pray Syria doesn't fall into that.

Excellent piece, Tam! I hope more people read this