The Blood Rep: Hasakah Prison Siege Break Down

On 20th January ISIS cells launched an ambitious assault on Sina prison in the Ghwayran neighbourhood in al-Hasakah, the provincial capital, in northern Syria. This part of the region is controlled by the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The Kurdish militant group is closely aligned to the PKK and supported by Western coalition forces to the great displeasure of its neighbour, Turkey, who view the SDF and PKK as terrorist organisations.

The SDF is viewed as an existential threat to the modern Turkish state. Turkey views the SDF as part of a Kurdish nationalist project which seeks to carve a state out of Turkish, Iraqi and Iranian sovereign territory as well as causing significant unrest within Turkey’s own Kurdish population. These dynamics need to be taken into account as we consider the latest prison siege.

The SDF, supported by British and US coalition forces, countered the prison assault which unlike previous prison revolts began by Islamic State cells penetrating the prison. The battle raged till the 28th of January. Film diffused on ISIS media platforms showed how its fighters swore to fight to the death, and took what seemed to be mostly Arabs judging by their tribal affiliations, as hostages.

During the siege there were also disturbing reports that children, presumably those belonging to ISIS members, were also incarcerated inside and were caught in the crossfire. It evoked memories of the Beslan school siege of 20041 and raised serious questions by western human rights organisations about the treatment of children in these SDF prisons2. Eventually many IS fighters surrendered but it came at a cost. According to the SDF: 44 SDF fighters, 77 prison guards, and 4 civilians lost their lives ISIS propaganda claim otherwise.

Whilst the ISIS assault failed militarily, it questioned the idea that this provincial capital which is of immense strategic and economic value is firmly under the control of the SDF3. It also suggested that ISIS was making a quiet resurgence or an attempt to reassert itself, albeit locally. In fact, this was inadvertently revealed by the SDF’s own propaganda output. For though the siege ended on the 28th January fighting and sweeping operations continues for cells, supporters and ISIS fighters.

Even if we assume that the SDF want to magnify the ISIS threat for their own interests, if we compare it alongside ISIS propaganda, it seems to indicate a considerable ISIS presence in their territory. During the days that followed, the SDF revealed that 9 wanted individuals alongside documents, weapons were seized in Abu Hamam and Abu Hardub in eastern Deir ez-Zur. Moreover suicide bombers of Turkmen and Iraqi backgrounds were also captured4. It should be noted that many of those arrested were in the same area that ISIS retreated to before their last stand in Baghuz and it would not be unsurprising that many of its members are still hiding in and around those pockets. 26 individuals were seized in northern Deir ez-Zur and were involved in smuggling. Bu Kamal was a famous entrepôt for smuggling goods between Syria and Iraq long before ISIS took over. The images posted by the SDF suggest that those captured were likely indigenous. In Raqqa province, 27 individuals were arrested and caches were found in camps and villages. As I write this the SDF is still making sweeping operations trying to identify militants and cells within their territory.

What does the prison attack reveal?

Local Support

It reveals that ISIS has local support although it may not necessarily be heartfelt. Why? As an example, Hasakah is ethnically diverse and has a large population of Arabs linked to the respective tribes. Many Arabs from Hasakah have long complained about discrimination and marginalisation after the SDF take over. This may be due to the fallout of the past where the late Syrian president Hafez al-Assad tried to arabise the borderlands in order to dilute the Kurdish population, resulting in ethnic tensions flaring up in times of crisis.

In such difficult times ISIS can draw on the discontent of the local populace and exploit those fissures. It is interesting that ISIS didn’t kill the hostages it captured publicly on its social media channels like it did in the past. This may be due to the hostages belonging to the Arab tribes and ISIS didn’t want to alienate those respective tribes they came from, for it might also harm their own local support base. What it also hints at, is that this latest success is symptomatic of a greater problem in the region.

Lack of Capacity

In August 2020 the Pentagon reported that 85 percent of prisoners - were held at two SDF prisons run in Hasakah and Shaddadi; each housed between 3,000 and 5,000 fighters. There are other jails in Malikiya, Qamishli and Tabqa; and more than a dozen others smaller jails that have been converted from existing facilities.

There were prison riots in March 2020, May 2020, and June 2020. The causes were: (a) COVID-19, (b) lack of due process, (c) access to families, and (d) prison conditions. The Pentagon put a plaster on the problem by providing $2 million dollars in aid for improved doors, cameras, riot gear and personal protective equipment but the problem remained unsolved5.

The problem is further complicated by the SDF allegedly using these prisoners as a bargaining tool for some sort of diplomatic recognition. It has made foreign countries not wishing to experience Turkish wrath unwilling to deal with the foreign fighters stuck inside SDF prisons.

However, the SDF does not have the capacity to process these detainees and these prisoners remain in limbo which the U.S Defense Intelligence Agency warned would allow ISIS to exploit these fissures. The Hasakah prison break appears to be a manifestation of this warning coming to pass.

There is no mechanism of demobilising or a way of reintegrating these prisoners back to civilian life. This results in ISIS being able to bring these fighters back into their ranks. After all, those fighters that are released have little option to do otherwise- they are in many ways seen as untouchables. Here, it is worth considering the Japanese approach to reintegrating former Yakuza gang members who want to return back to civilian life but are stigmatised by their past so that wider society do not want to re-integrate them6. In response the Japanese authorities have come up with a scheme that allows these gang members to work in approved firms who in turn receive financial incentives. In this way former Yakuza members can reintegrate back into Japanese society. Of course, the Japanese authorities are operating in a stable functioning society and the SDF are not. Nevertheless, this may be of interest to those wrestling with the problem of ISIS fighters languishing in prison, as the problems are not all together un-similar.

Moreover, demobilisation or processing ISIS fighters is only part of the problem. The ethnic, political and indeed religious fissures alongside competing aims of local and international actors, means that ISIS can move into spaces where no authority exists. They can incubate in-between the borderlands of Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

How to understand the Prison attack in Hasakah?

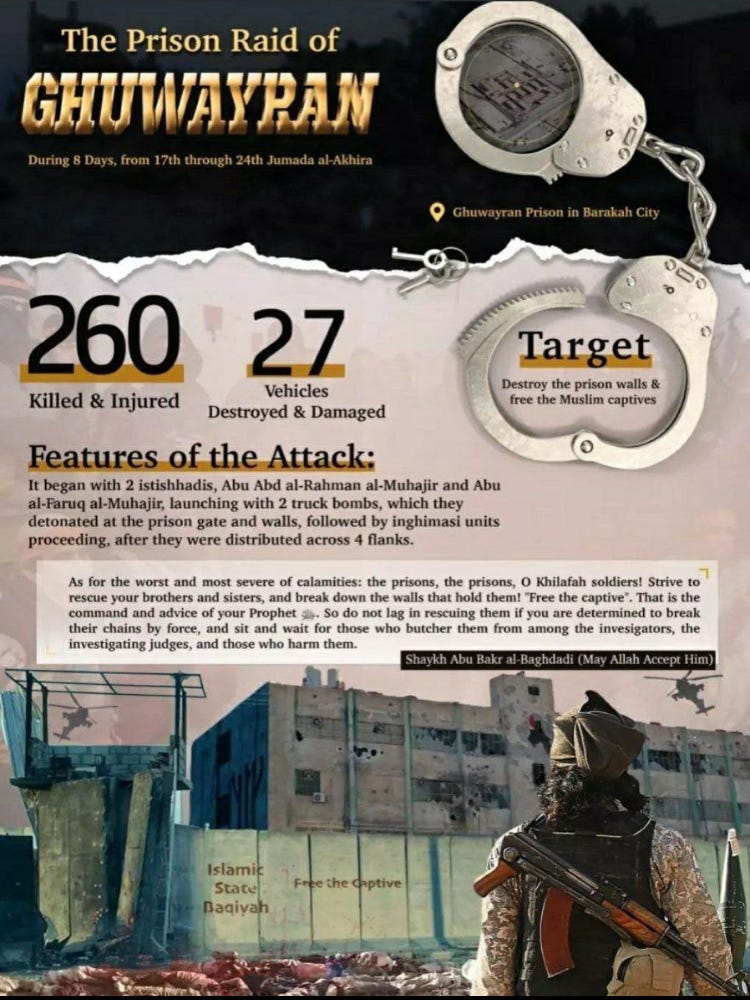

“The destruction of walls” as ISIS has called the latest prison break is in many ways nothing new. As early as 2021, ISIS newspaper, An-Naba, released an infographic entitled “We have not forgotten you”, outlining its numerous attempts at freeing its comrades. A video interview filmed two years ago with an ISIS prisoner recently re-upped on an ISIS forum says that it was a major concern for the leader of the Muslims i.e. the ISIS caliph to release prisoners.

ISIS is a militant organisation consisting of foot soldiers with family connections in the region. Freeing their loved ones who languish in the internment camps al-Hol and al-Roj, as well as prisons all over the region, is a priority for them on a human level. Many of the fighters have their wives and children in al-Roj and al-Hol camp. We have already documented previously, the sophisticated use of cryptocurrency in these efforts to free ISIS women and children7.

There are numerous Telegram channels which encourage Muslims to donate to release prisoners detained in northern Syria, and many within the Muslim community, though not supporters of ISIS, may be fooled into donating thinking them to be a genuine charitable act.

Historically, freeing Muslims imprisoned by “infidels” is seen as religiously sanctioned. You could even pay your zakat (similar to the tithe in the Christian tradition) to free them8. And some Muslims not fully aware of the complexities of the region could donate in order to free these women and children but ending up funding ISIS cells. There is no guarantee after all, that the money donated will reach the women and children in the camps. And perhaps this is the strongest argument for the international community to get involved in the repatriation of these detainees.

As discussed before, for Jihadists, spending time in prison is proof of their own righteous stance. There is a well known Prophetic tradition that says when God loves someone, He afflicts them with tribulation, and so their incarceration is interpreted as such. The Jihadists see themselves as emulating the Prophets, many of whom spent time in prison - Joseph in the dungeons of the Pharaoh and Jonah in the belly of the Leviathan. Moreover, Syed Qutb, Zaynab al-Ghazali, Omar Mokhtar, Malcolm X, Ayman al-Zawahiri, Omar Abdel-Rahman ‘the Blind Sheikh’, Abu Qatadah, Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Aafia Siddiqui, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and others from different Islamist movements have all been in prison.

It also follows that, since Jihadists are men of action, that their companions who are imprisoned should be freed by them. The recent example of British criminal, Malik Faisal Akram taking hostages in a Texas synagogue calling for Aafia Siddiqui’s release is a good reminder of precisely that9. Arguably, it has become a particular forte of Jihadist groups, especially al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQIM) and its successor ISIS. On the 6th of March 2007, AQIM succeeded in freeing 140 prisoners with an all out assault on Badoush prison. AQIM continued these activities until they evolved into ISIS who perfected the art. On the 21st of July, 2013 it freed over 800 inmates from the notorious Abu Ghraib prison seriously questioning the credibility of the Iraqi government10. The Hasakah prison break should be seen in the light of this tradition; an attempt to seriously undermine the credibility of the SDF and boost ISIS morale.

Nevertheless, this attack is significant both in its boldness and ideological ambition, especially considering that the caliphate was extinguished in Baghuz on 23rd of March, 2019 and the caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was killed in 27th of October 2019. The Hasakah prison break is the first attempt of ISIS trying to reassert itself in the region. What is interesting is that despite the death of its latest caliph, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi on the 3rd of February 2022 in Atmah, the celebration of the prison break continued on ISIS’ Telegram channels without it even acknowledging his passing or his importance.

This is probably because modern jihadism has moved away from a centrally controlled operation to becoming a movement which relies on “diffuse, de-centralised and non-hierarchical networks” as envisaged by the likes of Abu Musab al-Suri, one of the architects of global jihad in the 90s11. Nowadays Jihadists are self-operating, localised and fully autonomous- it is bandit-jihadism which is unaffected by the death of a central leader, and so whether Abu Ibrahim al-Qurashi lives or not, matters little.

ISIS is ironically living out the ideas of Carlo Pisacane, the Duke of San Giovanni, who believed that dramatic acts will sustain the movement rather than figures. And even though Pisacane was killed as he tried to land on the beach in Sapri, southern Italy, after being mistaken for a gypsy, his movement lived on and found expression in the Risorgimento etc. ISIS is trying to revive its flagging fortunes through bold action and, judging by the jubilation on its own forums, it is working. ISIS has already announced several attacks at SDF-held checkpoints seemingly emboldened by the event.

And so what the prison break in Hasakah celebrates is the revival of the fight, martyrdom and courage etc. The fact that the fighters wore red bandanas and called themselves the grandsons of Abu Dujanah, the famous warrior companion known for his red turban, is deeply symbolic and powerful to ISIS supporters. And the 3 page spread in An-Naba newspaper makes it abundantly clear that it was never about winning - it was about the boldness of the act, while the end result remained in the hands of God. The “Breaking of Walls” policy if you will, has its own ideological and emotive force which will boost morale for supporters as well as those inside the prisons. The message is clear: they are not alone and more is to come. And that is probably why the prison break of Ghwayran is important and will likely serve as an example for future operations.

Conclusions

In a region where there are different power centers with different agendas and a patchwork of various local actors; a fluid organisation like ISIS adept at asymmetric warfare will flourish unless something drastic is done. They are, to use an old cliché, the Hashashiyun or the Assassins of our times.

Moreover, those ISIS fighters that may wish to put down the gun, are not able to because there isn’t a mechanism to demobilise and reintegrate them into society. This gives the ISIS fighters a greater resolve to carry on. For instance, this author came across ISIS families who would like to return to their homeland and reintegrate, but due to the repercussions facing them, prefer to remain where they are in these ungoverned spaces.

The ultimate solution to the problem in the region is obvious; one needs to stabilise it. The region probably requires a massive influx of money, not dissimilar to the post-World War II Marshall plan. It would create jobs, prosperity and connect the people economically to each other, which would make the reopening of hostilities immensely harmful to their interests. But such things seem difficult to envisage in the current climate. In addition, whether there exists a political will for such a solution is also unclear, with so many competing interests in the region.

ISIS can serve the interests of various regional powers to destabilise and tip the balance of power in their favour, in the same way al-Qaeda, though antithetical to Iran’s vision, served the latter’s goals and agendas. And since the necessary political will is not in place, the triangle between Iraq, Syria and Turkey will remain the badlands and ISIS will remain its bandit king.

Beslan school siege: Russia 'failed' in 2004 massacre, BBC News, 13 April 2017

Jane Arraf, Teenage Inmates in Syria Lack Food and Medicine, Aid Group Says, The New York Times, 6 Feb, 2022.

Al-Shaddadi, in Hasakah province, is a major oil town and was captured by the Nusra Front in 2013 for that very reason. See Gaith Abdul-Ahad, Syria's al-Nusra Front – ruthless, organised and taking control, The Guardian, 10 July, 2013

Andrew Hanna, Islamists Imprisoned Across the Middle East, Wilson Centre, 24 June 2021

See Richard Lloyd Parry, Kita-Kyushu, Missing finger marks out ex-yakuza gangsters struggling to go straight, The Times, 4 February, 2022,

For an example see here on questions regarding using your zakat to free Muslims: https://islamqa.info/amp/ar/answers/130549

Dan Frosch, Texas Hostage Taker Identified as British Citizen Who Traveled to U.S. in Recent Days, Wall Street Journal, 16 January, 2022

See Trevor Cloen, Yelena Biberman and Farhan Zahid, Terrorist Prison Breaks, Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol 12, Issue 1, 2018

Brynjar Lia, Architect of Global Jihad, The Life of Al-Qaeda Strategist Abu Mus'ab Al-Suri, Hurst, 2009, p2